Natchez Trace Parkway celebrates 75 years

Published 12:31 am Sunday, May 12, 2013

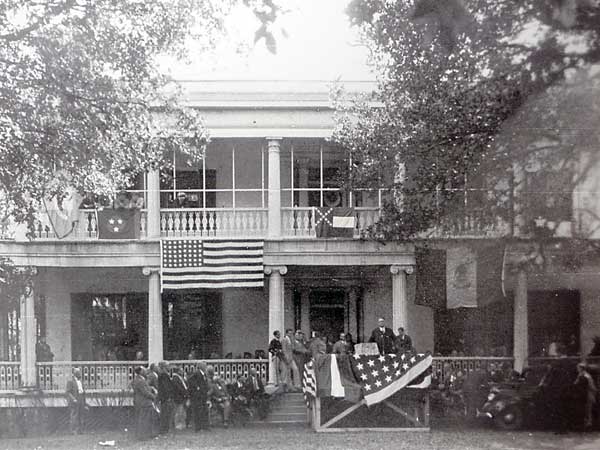

The Natchez Trace has changed since Roane Fleming Byrnes worked to get the old trail paved. At left, Byrnes stands in the old Trace. In bottom center, Brandon Hall served as the site of the inauguration of the parkway’s construction. Top center, visitor now travel up and down the parkway from allover the world.

NATCHEZ — Saturday marks the paradoxical 75th anniversary of one of Natchez’s oldest connections with civilization.

The National Park Service will mark this weekend the day in 1938 when the NPS assumed control of the historic Old Natchez Road — today known as the Natchez Trace Parkway — and began the process of turning the 444-mile stretch into the seventh-most visited U.S. National Park and one of only four scenic byways in the park system. Trace Interim Superintendent Dale Wilkerson said the parkway plays host to 5.6 million leisure visitors annually.

But travel on the Trace began long before 1938, or even the Mississippi colonial period. Jim Barnett, director of the Grand Village of the Natchez Indians, said Indian archeological sites along the length of the Trace date back 5,000 years.

“That really indicates that the Trace is an ancient trail or pathway,” Barnett said. “It’s a popular notion that the Trace started as a game trail, but the game trail story is completely false.”

- Roane Fleming Byrnes stands in an old section of the Natchez Trace as part of her many efforts to promote the Natchez Trace Parkway. Byrnes died at age 80 in 1970.

- Courtesy of the Memphis Commercial Appeal — Roane Fleming Byrnes stands in an old section of the Natchez Trace as part of her many efforts to promote the Natchez Trace Parkway. Byrnes died at age 80 in 1970.

- A promotional photograph for the Natchez Trace Parkway.

- An brochure advertising for a workshop in 1989 on the tourism potential of the Natchez Trace.

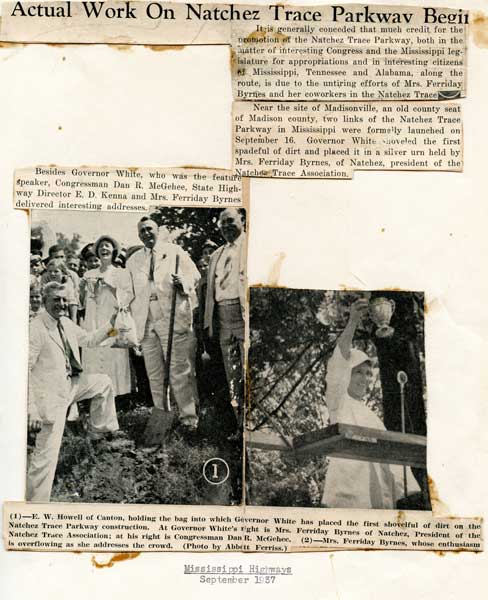

- Newspaper clippings from when the parkway construction began.

- Parkway construction in 1940.

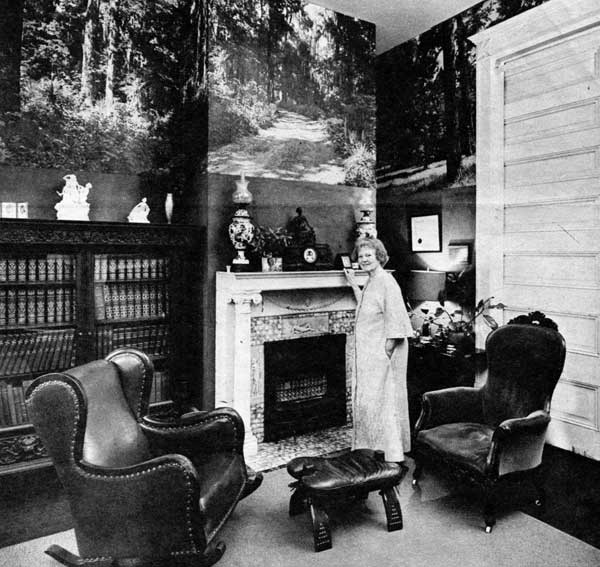

- Courtesy of the Memphis Commercial Appeal — Roane Fleming Byrnes stands in the room in her house at Ravennaside that featured murals of the completed Trace on the wall. This is where Byrnes was known to entertain gusets and lobbied for continued progress on the project.

- JAY SOWERS | THE NATCHEZ DEMOCRAT A car moves southbound on the Natchez Trace Parkway near the southern terminus of the historic roadway in Natchez on Friday afternoon.

- JAY SOWERS | THE NATCHEZ DEMOCRAT Bonnie Pylman, left, and Bill Daley look over a map of the Natchez Trace Parkway while stopping at the Old Trace Exhibit Shelter just 10 miles from the southern terminus of the historic roadway in Natchez on Saturday afternoon. The couple, who reside in Milo, Mich., are making their way back home after their annual winter trip to Mexico.

- JAY SOWERS | THE NATCHEZ DEMOCRAT A car moves southbound on the Natchez Trace Parkway near the southern terminus of the historic roadway in Natchez on Friday afternoon.

- JAY SOWERS | THE NATCHEZ DEMOCRAT A car moves southbound on the Natchez Trace Parkway near the southern terminus of the historic roadway in Natchez on Friday afternoon.

- Jay Sowers | The Natchez Democrat

When it started, what became the Trace was not in ancient times a single unified roadway.

“It was more of a series of interlocking trails that at times were probably some distance from the modern parkway,” Barnett said.

When the English settled in the Carolinas and the French established their Louisiana colonies, the existing Indian trails across the country became natural travel and trade routes for the colonists.

“The trails that made up the Natchez Trace were used by the earliest European explorers and military people and colonial people in the region,” Barnett said.

“Some of these trails were used by people seeking to trade with the Indians and to set up alliances with them, and later on the trails that really were not linked together became linked together as trade routes leading from the Mississippi area, back to Carolina down to Mobile, Ala., and New Orleans and of course to Natchez.”

As history progressed and land changed hands between colonial and then independent U.S. powers, the U.S. government saw the benefit of having access to the Trace.

“The first treaty between the U.S. and the Chickasaw Indians that was signed in 1801 was for the right to travel through the Chickasaw territory in northeastern Mississippi along the trail that became the Natchez Trace,” Barnett said.

That same year, the road was ordered improved by President Thomas Jefferson so it could serve as a military road to protect the nation’s interests at the port of New Orleans, Natchez Trace Parkway Association President Bryant Boswell said, and in 1803 — with the Louisiana Purchase — the road became an important tool in exploring the Louisiana Purchase.

During the War of 1812, the Trace was famously used by Andrew Jackson to move his troops, and during the U.S. Civil War Union Gen. Ulysses Grant’s Army of the Tennessee used it as they marched northward from Port Gibson to the Battle of Raymond.

During the peacetime years in the early 19th century, the Trace became a major — if sometimes dangerous due to the presence of outlaws — highway for those who floated boats down the Mississippi River to sell in southern markets to return home.

In the 1830s, the invention of the steamboat and a better road — the Jackson military highway — led to a decline in the Trace’s use.

“With the Jackson military highway being built, the Trace became not nearly as needed or in demand and it fell into disrepair,” Boswell said. “It served in the Civil War, but after that it was about to be grown up and some portions of it turned into county roads.”

In 1908, the Mississippi president of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Elizabeth Jones, proposed that the group place a marker denoting where the Trace ran through every county.

Another DAR member, Roane Fleming Byrnes, a Natchez native, took up the cause of a paved Trace. A member of the Natchez Trace Association, which had been formed in 1934 with that goal in mind, Byrnes lobbied for the Trace in Washington D.C., and hosted Congressional officials in her home.

“In a lot of ways, (Byrnes) is the mother of the Trace,” Boswell said.

The paved Trace was approved by President Franklin Roosevelt as a part of the New Deal parkways the same year the Trace association was formed, and the paving project started in 1937. The NPS was given command of the parkway the following year.

“He built it as a memorial to Andrew Jackson and all the men who had died on the Natchez Trace,” Boswell said. “What we have is a 444-mile cemetery, most of the dead being from the War of 1812.”

The first paved portion of the Trace, between Jackson and Kosciusko, didn’t open until 1951 because World War II disrupted the work, Boswell said, and the paving continued until 2005, when the final portions — from Jackson to Clinton, and between the Trace’s then southern terminus and Liberty Road at Natchez — were finished.

“When you really think that construction of the parkway began in 1938, it was an advanced highway for that time period,” Wilkerson said. “Even today one of the remarks we get is how nice the road is to drive on, its curves are smooth and gentle.”

“It lies pretty much lightly on the land. We didn’t go in there and do a lot of cutting and filling of areas; we pretty much put the parkway on the land as the land lays, which means that sometimes you come around a corner and there is something unusual in front of you.”

The Trace is more than just a roadway — it provides access to many historic sites, including preserved Indian and colonial archeological sites. And now that the parkway is paved, Boswell said that’s where the Trace association’s focus lies.

“Once the completion of the paving was completed, the parkway association lost some of its reason for existence, and so for the last three or four years we have really rejuvenated our mission to interpret the history and promote safety and recreation (on the Trace),” he said.

Recently, the association had a 10-day, 444-mile living history initiative commemorating Jackson’s military march, and actively works to promote safe driving along the parkway to allow for the recreational use of bicycles and jogging, Boswell said.

“We want to not only educate the next generation but to remind everyone that we are fortunate to have a national park running all the way across the state, and we need to understand the significance of it.”