Alumnus preserves headstones

Published 12:06 am Friday, June 1, 2012

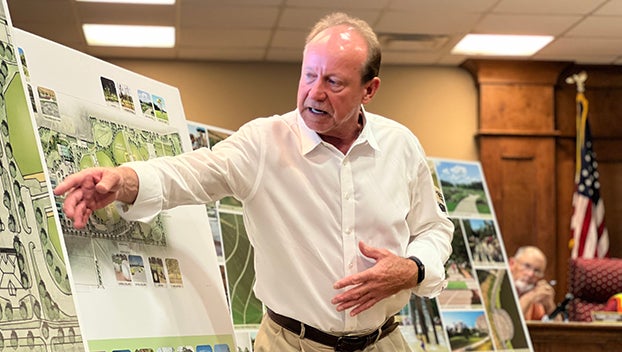

LAUREN WOOD / THE NATCHEZ DEMOCRAT — James Shaidnagle, who was at D’Everuex Hall Orphanage from 1955 until 1962, purchased 10 new gravestones from Natchez Monument to replace 8 of the marble ones of boys who were buried in Natchez Cemetery, and two for he and his brother Billy for when they pass.

By Mollie Beth Wallace

The Natchez Democrat

NATCHEZ — When James Shaidnagle walked across the gravel near Cathedral School’s D’Evereux stadium, he thought about the building he once called home.

Shaidnagle and his younger brother, Billy Shaidnagle of Lake St. John, were two of the last students to graduate while living at D’Evereux Hall in 1962 and 1965, respectively.

The building, an orphanage, was where Cathedral’s stadium is now.

Shaidnagle left Natchez after graduation, but came back in recent years.

Since his return, Shaidnagle discovered all that remains of his former home and school and its one-time residents — a plot at the Natchez City Cemetery — were in need of a little attention.

So Wednesday morning Shaidnagle helped place headstones — one for himself and his brother — in the lot where other orphans from D’Evereux Hall are buried at Catholic Hill in the Cemetery.

Along with the two personal headstones, Shaidnagle purchased new headstones to mark the graves of his fellow alumni.

The Natchez diocese of the Catholic Church, in keeping with provisions from the will of William St. John Elliot, founded the D’Evereux Hall Orphan Asylum in a small frame building on 35 acres on Aldrich and Pine streets in 1860. The orphanage was managed by men from Brothers of the Sacred Heart, a Catholic religious organization that had a division in Bay St. Louis at St. Stanislaus College.

A larger building, D’Evereux Hall, was completed in 1866 and sat atop the tallest hill in Natchez on the same 35 acres, which the Catholic Brothers and boys at the orphanage farmed.

Decades later, the Shaidnagle brothers rode to Natchez to take advantage of a chance for a better life.

Although they didn’t fit the orthodox definition of an orphan, the orphanage took the Shaidnagle boys in due to their family situation.

James Shaidnagle grew up in Greenville with eight younger siblings.

A student at St. Joseph Catholic School in Jackson, Shaidnagle said he was only 10 when one of the nuns at St. Joseph took an interest in him.

Shaidnagle said Sister Paulinus Oakes spoke to the Monsignor of the school on his behalf since she knew about his family situation.

“My father only had a sixth-grade education and things were tough,” he said.

When given the choice to move to D’Evereux Hall and attend school there, Shaidnagle said he didn’t even have to think about the decision.

“I knew that in order to not end up like my father, I had to get an education,” he said.

Shaidnagle said he remembers crying from homesickness his first year at D’Evereux Hall.

“I still remember the car ride coming over,” he said. “I can still see Monsignor and the priest in the front seat and Billy sitting with me in the back.”

But all the memories are not sad, Shaidnagle said.

“It seems like anything yucky was just erased,” he said.

“When I was there Brother Edgar (Gagnon) was in charge,” he said. “Brother Henry (Moulin) took care of the boys who were sick, and he was in charge of the clothes we had.”

Shaidnagle said out of all the Brothers there, Brother Henry sticks out most in his mind. Though the farming at D’Evereux Hall had dwindled, Shaidnagle said Brother Henry still maintained tomato plants and bees.

“(Brother Henry) would come in and say, ‘I want them Shaidnagle boys,’ and want us to help him,” Shaidnagle said. “But we would try to duck and hide because we knew we would lose all our play time working with Brother Henry.”

Shaidnagle said his days at the orphanage were very structured.

“Every second was accounted for,” he said.

While the Brothers originally taught the orphans themselves, by 1952 all boys attended Cathedral Grammar School.

Shaidnagle said he remembers starting each day with 6 a.m. mass and then walking down the street to Cathedral for school.

After graduating from Cathedral, Shaidnagle attended Jones County Junior College, and then he finished his degree at Delta State University in Cleveland.

With a degree under his belt, Shaidnagle said he moved to Missouri and began a teaching career that lasted 45 years and took him back to Mississippi and then to Illinois.

“I knew when I was in the fifth grade I wanted to be a teacher,” he said.

Teaching, Shaidnagle said, is the best opportunity to make an impact on someone’s life.

“You do the best you can,” he said. “Each day it’s about what you can do to help someone else.”

Shaidnagle said he’s always been a “hyper” person, and he said his students always wondered how he had so much energy.

“If you’re really enjoying what you’re doing you’ll go 90 miles an hour all day,” he said.

When the time came for Shaidnagle to retire, he said he knew where he needed to go.

“I always knew that if there was a place I could call home this is it.

“All the time I had been away you think you know where home is,” he said. “Most of the experiences that molded me occurred here.

“I have so many memories there at St. Mary’s. We would always sit in the front right, and I can go back and sit there and tear up anytime,” he said.

When he moved back to Natchez in 2009, Shaidnagle went out to the Natchez City Cemetery to visit the graves of several Brothers and orphans from D’Evereux.

Shaidnagle said the first thing he noticed at the site was an empty space.

“I went out, and I knew there were two empty slots there,” he said. “The first thing I did was try to find out how I could be buried there.”

After several phone calls, Shaidnagle said he finally got permission from the Archbishop in New Orleans.

While thinking about markers for the graves for himself and his brother, Shaidnagle said he was troubled by the condition of the site.

“You couldn’t even read the names on some of the orphans’ graves,” he said.

Shaidnagle then took it upon himself to purchase new markers for each orphan’s grave along with his and Billy’s.

The brick wall surrounding the plots was in dire shape as well, he said, so Shaidnagle enlisted the help of Curtis Johnson, who tore down the wall but managed to salvage the bricks and rebuild it.

Shaidnagle also sought out Cole Brown of Natchez Monument Company. Shaidnagle said Brown helped put the finishing touches on the site.

“He’s the one that suggested we put the stone in the middle to say ‘D’Evereux Hall Orphanage Burials,’ and that just set it off,” Shaidnagle said.

The motivation to renovate the site, Shaidnagle said, stemmed from his appreciation of the orphanage.

“I feel like everyone here took care of me,” he said.

Shaidnagle hopes that beyond preserving the memory of D’Evereux Hall, his efforts will inspire others to remember from where they came.

With so much work put into the site, Shaidnagle said he plans to keep it in good shape.

“I keep ant poison in my trunk,” he said. “And I went out and bought a battery-powered weed-eater yesterday.”

Though D’Evereux Hall is no longer standing, Shaidnagle hopes to perpetuate its memory by marking the site where many of its pupils were laid to rest.