Mississippi’s deer are due for a bad year of Hemorrhagic Disease, deer program coordinator says

Published 1:08 pm Wednesday, July 27, 2022

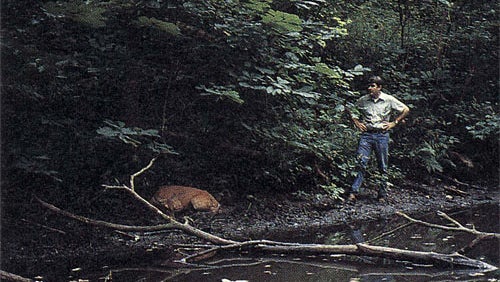

- Deer afflicted with Blue Tongue Disease or Epizotic Hemorrhagic Disease are commonly found near sources of water. They do this to combat the fever the ED brings. This is a disease which infects deer herds every year. (Courtesy Photo Southeastern Cooperative Disease Study)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

JACKSON — Late Summer is a peak time for deer to catch hemorrhagic disease (HD) in two forms, epizootic hemorrhagic disease or blue tongue disease. HD’s transmission occurs through midges, commonly known as gnats, biting the deer.

The disease is in response to the increased occurrence of midge vectors according to Deer Program Coordinator William McKinley with the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks.

McKinley said the disease is cyclic and every three to five years there is a fairly high mortality rate in the state’s deer herd. Already, he is getting reports of the disease in the northern part of the state for dead deer who show the common signs of having HD or blue tongue.

“This particular year we are coming off of five years of low years,” McKinley said. “About once a decade you have a bad outbreak so we are both due for a moderate outbreak and a severe outbreak. I expect it this year.”

Midges are more common in years of drought as they breed and lay eggs in receding mud flaps of ponds, rivers, lakes and creeks. When the water comes back up it destroys their lineage. It is possible the dry months of June allowed for a lot of Midges to breed although recently the state has received more and more rain each week which could slow down the Midges from breeding.

During summer droughts, deer are more likely to congregate at water sources because the water is limited. This increases their chances of being exposed to the biting Midges and HD. Deer can continue to show signs of HD into the winter but transmission typically ends with freezing temperatures.

There are three levels of HD in deer, peracute, acute, and chronic. The peracute form, characterized by its rapid onset, is the most dramatic. Deer may exhibit a loss of awareness of their surroundings, very high fever, difficulty in breathing, swelling of the head and neck, and the bluish coloration and swelling of the tongue that makes “blue tongue” a common name of the disease.

Death from the peracute form often occurs within 24 hours. In especially severe cases deer may die suddenly, even before any observable signs are evident. With the acute or chronic form of HD, deer live somewhat longer.

Animals may show hemorrhaging in the heart, rumen, and intestines. They could have ulcers on the tongue, dental pad, palate, rumen, and omasum. The lining of the rumen, in the stomach, may become ulcerated, scarred, or even eroded, which affects the deer’s ability to absorb nutrients from ingested food is compromised when significant amounts of papillae, the finger-like projections on the rumen wall, are lost. Emaciation can result, even in the presence of ample food resources.

McKinley said there are only two outcomes for deer who have ulcers from the disease, they either get better and recover or die. There is not much land owners or hunters can do to help deer fight the disease other than to keep their local herds healthy.

“Healthy deer can better combat hemorrhagic disease. There are seven strains of it and they all react similarly. If you can keep your deer healthy they will be better able to combat it,” McKinley said. “Something people may not know is when it comes through a herd every deer gets it. The vast majority get it and get over it. I remember one time we had a deer who had strains or ties to six different variants of HD.”

HD outbreaks kill off about 5 to 10 percent of the population and on occasion a local outbreak could be as high as 20 percent. He said the disease is limited by the range of the midge and a deer’s tolerance to HD is based on their history of exposure.

The longer HD is in a deer herd the more immunity is passed down from generation to generation. Deer with a northern lineage are typically more susceptible to mortality with the disease because the immunity was not passed down.

Mississippi’s deer herd has a variance in how often HD kills deer in the herd. Deer in South and Central Mississippi have a lower rate than deer in North Mississippi.

“The further north you go the less resistance you see to it,” he said.

HD poses no direct health risk to humans and is not directly transmissible to humans. However, deer may develop bacterial infections or abscesses from the disease and these could make deer meat not suitable for consumption. It is not recommended to eat the meat of deer who have died of unnatural causes.

It is likely you will find deer who are afflicted with HD near water as they try to fight off fever. This fever causes other things to happen to deer.

Many hunters are familiar with the hoof sloughing associated with the chronic form of hemorrhagic disease because the condition frequently persists into the winter during hunting season. Sloughing is an interruption of growth, resulting from high fever, often causing the hooves to appear broken or ringed.

In extreme cases, the tips of the hooves will actually slough off. Debilitated deer may crawl on their knees or even push along on their chest, resulting in additional lesions on those areas.

He said they ask hunting clubs in the Deer Management Assistance Program to look for signs of hoof sloughing so they can determine pockets of HD outbreaks.

If you observe a deer with any of the symptoms listed in this article, report it immediately to any of the three Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks regional offices or the main office in Jackson.

“We are due for a bad year. There isn’t anything we can do to help the deer,” McKinley said. “We want people to know about HD and how to report deer who have it. We sample every deer we can sample for Chronic Wasting Disease or HD. Hemorrhagic disease requires a live virus to be sampled and it dies soon after the deer dies.”