Byrne found himself in midst of Mississippi State’s racial battles

Published 4:24 pm Tuesday, May 25, 2021

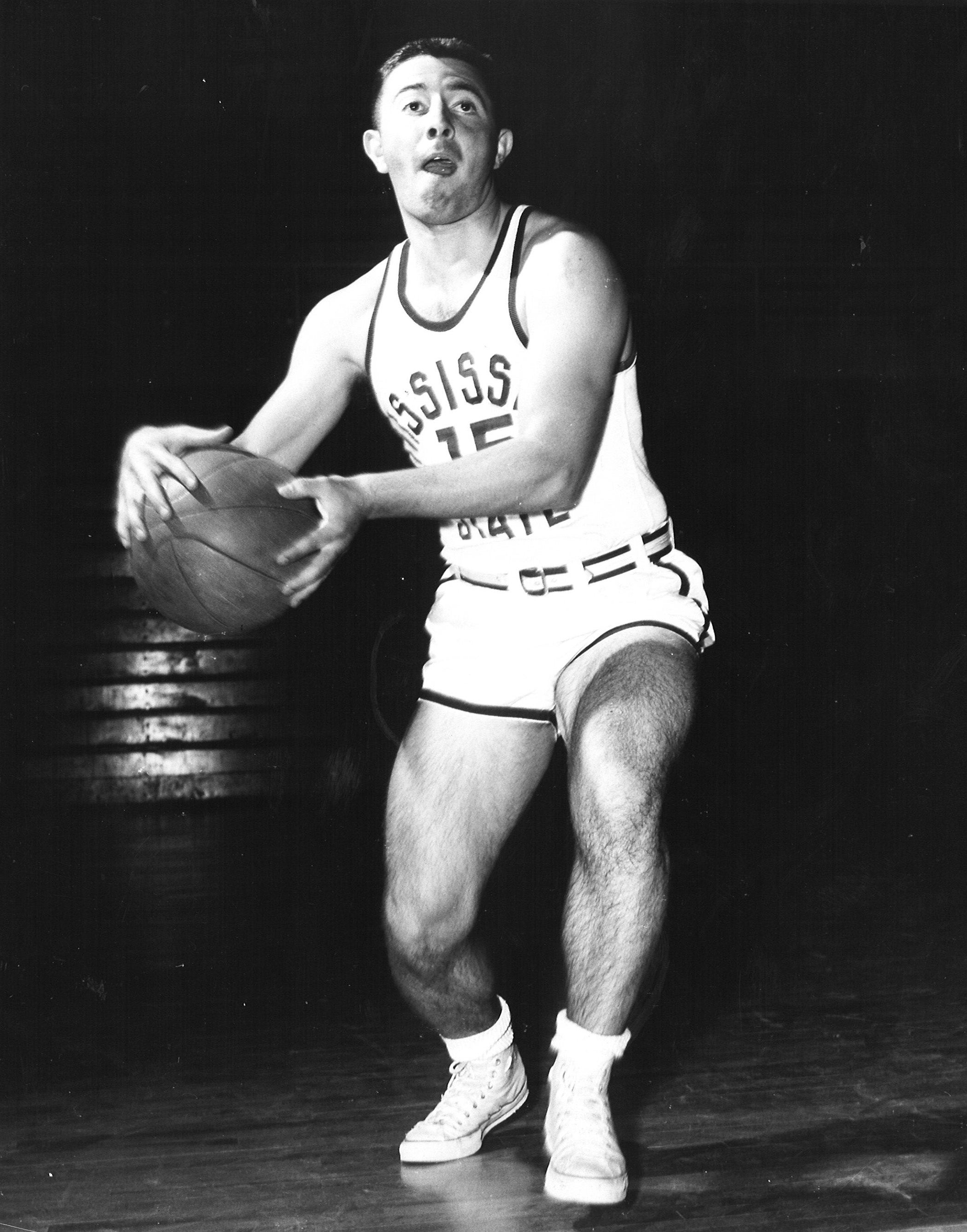

- Tony Byrne played on the Mississippi State basketball team in their 1954-56 seasons. (Courtesy Photo | Mississippi State Athletics)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Editor’s note: This story is the second part of a two-part series on Tony Byrne’s athletic career in college.

Mississippi State’s basketball team faced racial and political battles in 1956, as did most in the South.

Former Natchez Mayor Tony Byrne found himself along with Kermit Davis and Bailey Howell in the midst of those battles.

Byrne said people might know about the 1963 team, which played in the NCAA Tournament against Loyola Chicago in the “Game of Change.”

Mississippi State had to sneak out of Starkville in the cover of darkness to play in the tournament. What people might not know is Mississippi State had played against integrated teams in secret for eight years before the “Game of Change.”

In 1955, Byrne said he was with the team when they played in a Charlotte, S.C., Invitational. Before the tournament, the teams got together at a fancy restaurant, he said.

“They served prime rib and that was the first time any of us had ever seen a prime rib. It looked like it was raw,” Byrne said. “We played in that tournament, I don’t think we went very far, but we won two or three games. We played against some Blacks. I think Davidson had some Blacks, and Phoenix had some Blacks. Of course, it didn’t bother any of us. We didn’t think anything about it.”

No one knew about the games against integrated teams in 1955, he said. Jason A. Peterson’s book “Full Court Press,” which is about Mississippi State’s battle to play in the NCAA tournament and the media coverage of integrating college basketball, does not mention those games.

Peterson’s book begins with Jones Community College playing an integrated Compton Community College in the Junior Rose Bowl in December 1955. According to the book “Full Court Press,” this game prompted Mississippi Rep. R.C. McCarver of Itawamba County to propose a bill prohibiting collegiate teams from competing in integrated competition in January 1956. McCarver’s bill was not passed and did not become law.

Instead, the state college board and the state legislature formed a gentlemen’s agreement prohibiting collegiate teams from competing against integrated teams. This agreement was not law, but it was enforced as such by the legislator and college board.

Byrne was a junior in 1956 when Mississippi State traveled to Evansville, Indiana, to play in an invitational. He said the Bulldogs defeated Denver —an integrated team— and scheduled to play in the finals against the University of Evansville.

“Babe McCarthy was the head coach at the time,” Byrne said. “He told us when you get through eating, come up to my room. Don’t go out for a walk like you usually do. We all got there, and he said ‘Boys we are pulling out of the tournament and going home.’ Of course, we all said ‘No, we’re not. We are going to stay here. We worked hard to get here. We deserve to try and win this thing.’”

McCarthy told the team the state legislature wanted them home. Byrne said they were confused because they did not understand what the legislature had to do with them playing. He later learned the legislature controlled the funding for the school, and if Mississippi State had stayed, they would have cut funding for the College.

McCarthy ordered the players to board the bus with their roommate because the media in Indiana knew about the team pulling out. Byrne said his roommate at the time was Mike McRaney. McCarthy told the players to keep their mouths shut as they boarded the bus.

“One guy (a reporter) got behind us on the bus and said ‘Boys I’m from the south. I understand your thinking.’ We did not say a word. We did what the coach said,” Byrne said. “Finally, he had enough and said ‘What they are saying here is you are afraid to play against (N-word).’ We didn’t say a word. Of course, it wasn’t true because we had already played against Black gentlemen. (The reporter) said something to the assistant coach and took a swing at him and that is when the police came in.”

Officers took away the bus driver’s keys and driver’s license. At this point, most of the team was on the bus, Byrne said. Fans at the tournament were throwing rocks and shaking the bus because they were mad. He said the team made up of 18- to 20-year-olds did not understand what was going on.

He said his understanding later is that McCarthy called Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett and had him call Indiana’s governor to let the team go.

“We could not understand why we had to come home,” Byrne said. “Of course, having worked in politics, I understand it now, but not then. All we cared about was playing ball and winning. It upset us at the time. It took us probably a month to settle down.”

He said the experiences in 1955-56 changed his worldview after growing up in the segregated south. It shaped his philosophy on life and helped him when he pursued politics.

“I had no qualms about going to Black churches,” Byrne said. “Politicians in those days would not go. If you did go, the Klan would throw a paper out on you, which they did on me a few times. That one instance (in 1956) alone changed me. It changed my thinking.”