Local journalist chronicles cold-case investigations in book

Published 12:05 am Sunday, October 9, 2016

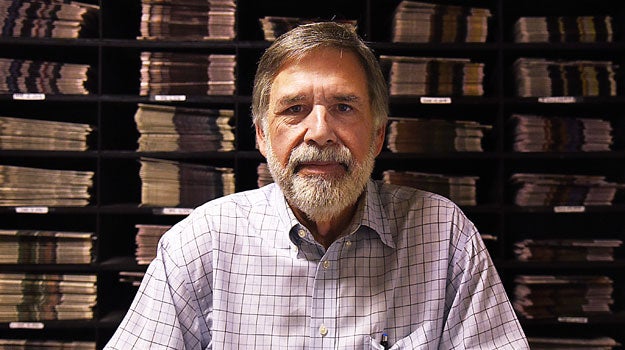

- Nicole Hester/The Natchez Democrat — The investigative work of Concordia Sentinel editor Stanley Nelson made him a finalist for the 2011 Pulitzer Prize in local reporting and led to the recently released book, “Devils Walking,” published by Louisiana State University Press.

FERRIDAY — In nearly a decade, what started for Stanley Nelson as a single newspaper article about a Civil Rights era murder grew into hundreds of interviews and stories — and now a book — detailing his investigation into eight civil rights cold cases.

The Concordia Sentinel editor chronicles his investigation in his newly released book “Devils Walking.”

Nelson’s work began with what he thought would be one story in February 2007 after he learned from co-worker Lesley Capdepon that the FBI and Department of Justice were reexamining cold civil rights cases.

The name of a Ferriday man — Frank Morris — was one of a handful of local names on the list.

Morris died in 1964 after four days of suffering from third-degree burns on 100 percent of his body. The injuries came after a group of Ku Klux Klansmen burned down his shoe shop in the middle of the night, with him inside.

“I really thought it would be one story,” Nelson said. “I thought it was so long ago and too far back for anyone to do anything.”

Nearly 10 years later, Nelson has read thousands of pages of FBI files, interviewed hundreds of people, from relatives of victims to suspects in the murders.

Nelson was named one of two finalists for the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for local reporting and was the recipient of the Gish Award from the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues for “courage, integrity, tenacity in rural journalism.”

In “Devils Walking,” Nelson covers 1960-1967 and eight murders linked to the Silver Dollar Group, a particularly violent offshoot of the Ku Klux Klan. The group, Nelson said, believed the KKK was not making the progress needed to stop the Civil Rights Movement and took their operations underground, carrying only a silver dollar as a sign of membership.

“They were terrorists,” Nelson said.

The backdrop of the book is the Civil Rights Movement and the local events surrounding the movement and what the Klan was trying to do to stop it.

“And (it’s about) all the carnage and terrible things that happened as a result,” Nelson added.

The book also offers a fairly in-depth history of local law enforcement, Nelson said, with stories of good cops and bad cops.

“It mentions by name some of these bad cops … who were either Klansmen themselves or working with the Klan,” he said.

“Devils Walking” took approximately two or three years to write, Nelson said, and came after the encouragement of others who had helped with his investigation.

Nelson’s work was aided by the Syracuse College of Law Cold Case Justice Initiative, members of the Civil Rights Cold Case Project from around the country and Canada and journalism students who have worked as interns at the Sentinel.

“They kept saying, ‘You know you’ve got a book here,’” Nelson said. “It took me eight years to totally understand what I was able to write in the book, because it was all very complicated.”

The book is heavily footnoted, Nelson said, to ensure accuracy.

“And in case anyone wants to continue the work, they have the resources,” he said.

In the years since he began investigating the cold cases, Nelson said he has seen many lessons that can come from that particularly dark era of American history.

“There are a lot of lessons, but one of the most important is that with every murder case, we must try to make it right again,” Nelson said. “Everybody within the community has a responsibility to see that justice happens, even if it’s through getting out and voting for the elected officials, the sheriffs and district attorneys, you know will do the work. We all have a responsibility. We can’t just depend on others to make sure justice will happen.”

The families victimized by the Civil Rights era crimes are no different than any other families, Nelson said, who would want to know what happened to their loved ones.

Through his investigative work and writing of “Devils Walking,” Nelson said he hopes the families of the victims know there are people out there who care that they see justice.

“For me, I want the (Wharlest) Jackson family and the Morris family and all the other families to know that I’m sorry for what happened. I’m sorry that justice failed them, and I tried to understand what it must have been like,” Nelson said. “I want them to know that there are people who care about their loss.”

Although 50 years have passed, some problems that exist in communities today, Nelson said, can be linked back to the injustice that accompanies many unsolved civil rights crime cases.

“I think some of the problems we have today are related back to these days when we have so many cases of unsolved crimes,” Nelson said. “The fact is that these kinds of crimes … they don’t go away within these families. The thing I took away from it, just as much as anything, is imagine that someone you love is murdered, and it seems like nobody in the world cares a bit about it but you.”